Children tripping over toys, bumping into tables, knocking over the block tower if this sounds like your preschool room, the problem is probably bigger than “they’re just energetic”. Without enough focused Spatial Awareness Activity built into the day, many children are simply guessing where their bodies are in relation to furniture, friends, and materials, and the environment keeps setting them up to fail.

The impact isn’t just a few extra bumps. Small accidents pile up in your incident log. Certain children get a reputation as “rough” or “careless” and start avoiding busy areas. Staff spend their energy on constant “watch where you’re going” reminders instead of calm, meaningful interaction. Underneath all that noise, early maths, handwriting, group games and even basic confidence are being shaped by how well children can judge distance, size and position.

This article will introduce ten space awareness activities designed for preschool children that require minimal preparation, and how to cleverly integrate these activities into your daily teaching routines, such as lining up, snack time, outdoor play, and tidying up. You will learn how these simple yet consistent activities can help children move more safely, understand space more clearly, and build the confidence they need for future learning.

What is Body Space Awareness in Childhood?

If you watch a group of three-year-olds for more than a few minutes, you can almost “see” spatial awareness at work. Before talking about any spatial awareness activity, it helps to pin down what we’re actually trying to grow.

At its simplest, spatial awareness is a child’s sense of where their body is in relation to objects, people, and boundaries around them. In early childhood, it’s not an abstract “skill”. It’s a lived, physical thing: how wide they think they are, how close they can stand to another child, how they judge distance when they run or throw. Psychologists usually break it into a few pieces, but in a preschool room, they blend.

Understanding Perceptual Motor Skills

How the brain and body work together to navigate the physical and social world.

Body Schema

The subconscious ability to track the position of your limbs and head without needing to look at them.

Spatial Boundaries

The intuitive sense of physical distance between yourself and others in social environments.

Spatial Relations

Processing positional logic—understanding concepts like in, out, under, behind, and between.

Temporal Awareness

Judging the timing and speed of actions—knowing when to start, when to accelerate, and when to stop.

There’s a strong link between spatial skills and later success in STEM fields. Longitudinal research from early years into primary has shown that children who do well on spatial tasks tend to perform better in maths and problem-solving later on. The detail of those studies is more technical than most nursery managers ever need, but the message is simple: this isn’t just about not bumping into tables. It’s about how children will later understand number lines, geometry, maps, even diagrams in science.

In the next section, I’d like to look more directly at why spatial awareness matters so much in a preschool room, not just for the children, but for safety, staffing, and even how parents perceive your quality.

Why Spatial Awareness Matters in Preschool Rooms

If you walk into a preschool room at peak time, somewhere between morning drop-off and snack, you can almost feel who is comfortable in the space and who isn’t.

Some children slip between tables without even looking down.

Some stop themselves just short of crashing into a chair.

Some move like the room is always a size too small for them.

That’s the importance of spatial awareness in preschool in real life, not in a textbook. It shows up in tiny, constant decisions: where to put a foot, how far to lean, whether there’s enough room to run. And those tiny decisions add up, both within the child and in your risk log.

Impact on learning and pre-math skills

A child working out “which pile has more” is comparing size and layout long before they touch written numerals. Matching one plate to one cup at snack time is one-to-one correspondence in disguise. Even following print from left to right is a spatial job: eyes tracking in a precise direction, line after line.

Years of research point to the same conclusion: early spatial skills are closely linked to later mathematical and problem-solving abilities, and well-designed spatial awareness activities are highly beneficial. They not only help children navigate their environment more effectively but also make abstract mathematical concepts easier to understand years later.

Safety and accident risks in crowded classrooms

The safety angle is usually the one that lands hardest with managers. A room full of three- and four-year-olds is, by definition, a moving environment. Bodies weaving, chairs scraping, toys migrating from one zone to another. Even with excellent supervision, a lot depends on each child’s moment-to-moment sense of space.

Children with shaky spatial awareness are the ones who seem to “find” table edges with their hips. They’re the ones who trip over a single stray block that ten other children walk around. In line-ups and transitions, they drift, bump, tangle. None of this is malicious, but it shows up in your accident forms.

Social interaction and confidence in group play

The last layer is the quietest, and in some ways the most painful to watch. Shared play is all about reading the space between people. A child joins a circle and instinctively leaves just enough gap for someone else to sit. They rush past a tower of blocks and adjust their path at the last second. In tag, they slow down as they get close, rather than ploughing straight through another child. When spatial awareness is weaker, the social cost starts early.

Children remember who “always ruins it”. You will hear the same names come up when something gets broken or a game falls apart. Over time, some of those children begin to pull back from active play, deciding that it’s safer to hang back than to be the one everyone tells off.

How spatial awareness develops in young children

If you are responsible for operating a center, it’s best to consider things from the perspective of different stages of spatial awareness development, rather than expecting two-year-olds and five-year-olds to do the same things in the same way. The nervous system, vision, balance, and strength are all developing and changing rapidly, so what might seem like “clumsy” behavior in one year may be perfectly normal, but if the same behavior appears in an older child, it could be a real warning sign.

Therefore, instead of focusing on exact ages, it’s better to think in terms of general age ranges. For example, toddlers who are just beginning to become familiar with their own bodies, preschoolers who are starting to explore space more consciously, and older preschoolers who are better able to manage themselves in group settings and no longer require as much adult assistance.

At each age range, there are some typical milestones in spatial cognitive development for toddlers and preschoolers. These are not test standards, but rather like signposts: “Yes, most children are roughly at this stage,” or “This seems to be out of sync with their development in other areas.”

And underneath all of it, spatial development and motor milestones are tightly tied together. When a child’s gross motor skills are delayed, their spatial skills usually are too. When fine motor control grows, their ability to plan small movements in space tends to follow.

Key Developmental Milestones for 2-3 Year Olds

For children aged two to three, you will typically observe them in the stage of becoming aware of their own bodies. At this stage, many spatial awareness activities are closely related to their bodies. They learn how to squeeze through narrow gaps, understand their body width, and how to lift their feet to climb small steps, beginning to understand concepts like “inside,” “on top,” and “outside” in a real and concrete way.

You will see children crawling through tunnels and under tables or climbing onto furniture simply out of curiosity, and then hesitating because they don’t know how to get down.

Key Developmental Milestones for 3-4 Year Olds

Children aged three to four are in an interesting developmental stage. Their physical abilities are greatly enhanced, but their judgment is still developing. At this age, you will typically observe children engaging in climbing, balancing, and jumping with more conscious intent rather than random, impulsive movements, and they are better able to control their speed of movement in familiar spaces. Their understanding of spatial terms is also deepening.

The development of spatial awareness at this stage is more evident in organizational abilities than in basic survival skills. Children begin to arrange objects, create patterns, and organize objects into rows or groups. They may begin to show distinct preferences; some children enjoy building and constructing, while others prefer drawing roads and maps.

Key Milestones from Ages 4–5+

By ages four or five, many children appear perfectly normal on the surface; they move freely, actively participate in group games, and can navigate a room without much assistance. However, this is also the age range where subtle differences in spatial awareness development begin to become more significant.

Typical abilities at this age include walking through a crowded room without bumping into others most of the time and adjusting their position in a circle or line without constant adult reminders.

Children at this age can usually understand concepts like “between,” “around,” and “through” in concrete situations and can imitate more complex arrangements of objects. They can begin to apply knowledge learned in one spatial awareness activity to another context.

Early warning signs of delayed spatial awareness

The tricky part is drawing a line between “a bit clumsy” and “we should look more closely”. Children develop at different rates; there’s always a wide normal range. But for nursery managers and room leaders, having a rough sense of early signs of spatial awareness delay makes it easier to decide when to adjust expectations and when to seek further input.

Some patterns that are worth paying attention to, especially if they persist over months and across different environments:

- The child bumps into furniture, doorframes, or other children far more often than peers of the same age.

- They struggle with basic stairs (going up and down with alternating feet) long after most classmates have mastered it.

- They avoid or quickly abandon puzzles, construction toys, and any activity that involves fitting pieces together.

- They seem confused by simple positional instructions even when the language has been taught and modeled repeatedly (“under the chair”, “on top of the box”).

- Their drawings and writing are very cramped or float all over the page, out of proportion to their age and exposure.

- In group games, they frequently misjudge distance and speed – running straight into others, stopping too early, or too late.

Taken individually, these signs don’t necessarily indicate a serious problem. However, if these signs appear together, especially if they are accompanied by more widespread developmental delays in motor skills, such as walking late, persistent balance difficulties, and difficulty coordinating movements on both sides of the body, then it should be taken seriously, and a more systematic observation should be conducted.

10 Spatial Awareness Activity Ideas

When most people think about a spatial awareness activity in preschool, the brain goes straight to an obstacle course and stops there. In reality, the day is full of chances to use space: on the floor, at tables, in doorways, even between chairs. These ideas stay very practical: what to set out, what to say, and how it looks in a real room. No posters, no fancy equipment unless you already have it.

You can treat them as a menu. Some work better in a big open hall, some in a small city nursery, some indoors on a rainy day.

Obstacle courses

This is the classic spatial awareness activity most teams already know: children moving through a simple path where they have to go over, under, around, and along. The focus here is on how the route is laid out and kept clear, so it actually works in a busy room.

What you need:

- Chairs, tables, benches

- Cones, hoops, floor tape, or cushions

- A clear start and finish point

How to set it up:

- Create a simple route: around a chair, over a cushion, under a table, along a taped line.

- Leave enough space between each station to prevent the children from crowding together.

- Mark the start and end with a hoop, line, or picture.

How it runs:

- One child starts at a time, or a small flow with space between them.

- You give very short instructions: “Under the table, around the cone, along the line, then back.”

- Children follow the same route several times, so it becomes familiar.

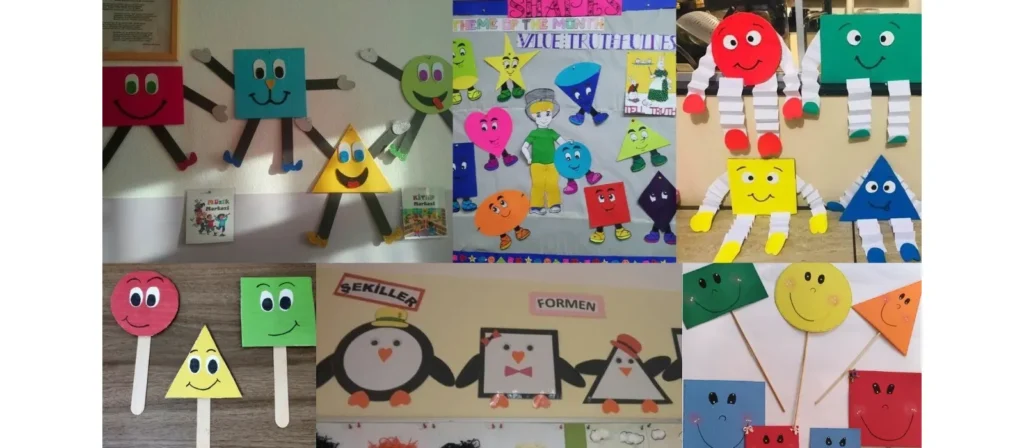

Crafts using shapes, sizes, and positions

This is a relatively quiet spatial awareness activity, cleverly integrated into regular craft time. Children still need to decide where to place objects, how far apart they should be, and which objects go on top or underneath, but they experience it simply as making a picture.

What you need:

- Pre-cut paper shapes in different sizes

- Strips of paper, glue sticks, plain paper

- Optional: simple picture models

How to set it up:

- Put shapes in shallow trays by type or size.

- Give each child a sheet of paper and a glue stick.

- Place one or two very simple “example” pictures on the table if you want.

How it runs:

- Offer a prompt: “Make a house”, “Make a city”, “Make a robot”.

- As children stick shapes, you comment naturally on where things go: “You put that circle on top”, “Those windows are close together.”

- Some children copy the model, others create their own layout. Both are fine.

“Simon Says” with spatial directions

This version of “Simon Says” turns the whole group into a moving spatial awareness activity. Children listen for location words and match them with body movements in real time, without needing any resources.

What you need:

- A clear space where children can stand without bumping

- A few chairs or tables nearby to use as reference points

How to set it up:

- Children stand in a loose circle or scattered with arm’s-length space.

- You stand where you can see everyone easily.

How it runs:

- Play as a spatial version of Simon Says:

- “Simon says touch your toes.”

- “Simon says put your hands above your head.”

- “Simon says stand next to a chair.”

- “Simon says take one step back.”

- You can drop the “you’re out” rule if it upsets the group and keep it as a following-instructions game.

Building and block play

The block area is already doing a lot of spatial awareness activity work. With a few tweaks, it becomes a deliberate place for children to experiment with height, balance, inside/outside, and simple structure copying.

What you need:

- A variety of blocks, unit blocks, Duplo, and wooden bricks

- A clear floor space and organised shelves

- Optional: photos of simple structures

How to set it up:

- Arrange blocks by type and size on open shelves.

- Mark a building area on the floor so that constructions are less likely to be knocked.

- Place one or two printed photos of bridges, towers, or walls nearby.

How it runs:

- Children choose blocks and build freely within the marked area.

- You sit nearby and talk about what they are doing: “You put a long block across two short ones”, “That tower is taller than you.”

- Sometimes you invite copying: “Can we make something like this picture?”

Floor and jigsaw puzzles for spatial problem solving

Puzzles are a focused, low-noise spatial awareness activity. Children rotate, flip, and slide pieces, testing what fits where. It’s ideal for small spaces and quieter corners.

What you need:

- Large floor puzzles

- Smaller jigsaws with 12–24 pieces

- A mat or a low table

How to set it up:

- Lay puzzle pieces out with the picture side up.

- Keep the finished picture or box lid visible.

- Make sure there is space for at least two children to work side by side.

How it runs:

- Children choose a puzzle and bring it to the mat or table.

- You sit with them at first and model simple strategies: “Let’s find all the corner pieces”, “This edge looks straight.”

- Children rotate pieces, try them, and adjust until they fit.

Outdoor classroom games and sports activities

Outside, spatial awareness activity ideas can be bigger and faster. Children judge distance and speed across a wider space, using cones, lines, and natural features as reference points.

What you need:

- Cones, hoops, chalk, soft balls, or beanbags

- Any lines or markings already in your outdoor space

How to set it up:

- Mark simple routes or zones with cones or chalk.

- Keep one area for running, one for throwing, and one for balancing if space allows.

How it runs:

- Choose one focus at a time

- Run between two lines and stop when you hear the signal.

- Throw objects at a hoop or wall from different distances.

- Walk along a straight line or a low balance beam without stepping outside the lines.

- Give clear start and stop instructions to prevent the group from becoming disorganized.

- Give clear start and stop cues so the group doesn’t dissolve into chaos.

Measuring distances and comparing lengths in the room

This type of spatial awareness activity sits between maths and movement. Children use their bodies or simple objects to “measure” the room and compare routes in a very concrete way.

What you need:

- Blocks, Duplo bricks, or strips of paper

- Chalk or tape (optional)

- A few obvious landmarks in the room (door, window, carpet edge)

How to set it up:

- Choose two or three “routes” to measure, such as door to carpet, table to shelf.

- Decide on a unit: footsteps, blocks, bricks, or strips.

How it runs:

- Ask children to count how many steps or blocks it takes to cover each route:

- Walk from the door to the window and count your big steps.

- Line blocks from this chair to that shelf.

- You note or say the numbers out loud: “Door to carpet: eight big steps.”

Action songs and movement rhymes

Action songs turn circle time into a moving spatial awareness activity without changing your whole plan. Children match words like up, down, in, out with their bodies in a predictable rhythm.

What you need:

- A few familiar songs with actions

- A clear space for standing or sitting in a circle

How to set it up:

- Children sit or stand where they can move their arms without hitting others.

- You choose two or three songs to repeat regularly.

How it runs:

- Use songs like “Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes” or “If You’re Happy and You Know It”.

- Add simple spatial directions:

- “Hands up high, hands down low.”

- “Step in, step out, turn around.”

- Keep the pace steady so children have time to follow.

Treasure hunt and “find it” spatial games

Treasure hunts turn the room into a giant spatial awareness activity without looking like “work”. Children search using clues that point to positions: under, on, behind, next to.

What you need:

- Small toys, picture cards, or coloured counters

- Hiding spots at child height

How to set it up:

- Hide objects under, behind, next to and on top of things around the room.

- Decide whether the hunt is for the whole group or for small teams.

How it runs:

- Give simple verbal clues, one at a time:

- “Look under something you can sit on.”

- “Find a card behind something soft.”

- “There is a treasure next to a bookshelf.”

- Children search, bring items back to a basket, and wait for the next clue.

Small-world and role-play setups

Small-world and role-play corners are ideal for a gentler spatial awareness activity. Children organise roads, furniture and people in miniature, which is often less overwhelming than organising their own bodies.

What you need:

- Road mats, cars, and small buildings

- A dollhouse with furniture and figures, or a small “town” built from blocks

- A home corner or pretend classroom

How to set it up:

- Arrange a simple scene: a few roads, a couple of houses, some empty space.

- Keep extra pieces in shallow trays so children can add to the layout.

How it runs:

- Invite children to move cars and figures around with gentle prompts:

- “Park the car between the two houses.”

- “Put the bed against the wall so people can walk past.”

- “Line the chairs up in front of the table.”

- Watch how they organise the space and adjust pieces as they play.

Developing spatial awareness in the classroom

In most nurseries, the big change doesn’t come from adding more toys. It comes from looking at what you already do and quietly bending it towards space. Lining up, choosing a spot on the carpet, getting coats, clearing plates – every one of these moments can carry a spatial awareness activity without adding a single minute to the timetable.

If teachers view spatial skills as an extra task, effectively developing these skills will be difficult. But if they can integrate spatial skills into familiar daily activities, it will become a habit. Even without formal lessons specifically focused on spatial skills, the classroom itself will begin to serve an educational purpose, which is key to achieving real progress.

Using everyday routines as spatial awareness activity moments

Daily routines are reliable because they repeat. That makes them perfect places to hide a spatial awareness activity. Children line up for the bathroom or outdoor play anyway; the only question is whether they do it in a random clump or with a bit of thought about distance and position. Small tweaks to how you ask can turn a dull transition into a quiet practice round.

Some groups cope well with extra layers: you might tape simple footprints on the floor, or mark boxes on a cupboard door. Others need it gentler, with just one or two spatial cues repeated over weeks. The aim isn’t to turn every moment into a mini lesson. It’s to let the child’s internal map update bit by bit while the day moves on as normal.

Teacher language: modeling spatial vocabulary in instructions

Teacher language is probably the cheapest tool you have. You’re giving instructions all day anyway; folding spatial words into those sentences turns every reminder into a tiny spatial awareness activity. Instead of “Put it back”, you say “Put it back on the shelf, next to the blue box.” Instead of “Come here”, you say “Come and stand in front of me.” Same effort, different impact.

Differentiating support for children at different levels

Not every child in a class needs the same amount of spatial challenge. Some need help just finding a safe place to sit; others are ready for quite complex routes and instructions. Differentiation here is less about worksheets and more about how you pitch a spatial awareness activity to different children without making that obvious to them.

You might shorten the route or stand closer for a child who bumps into everything, giving them fewer turns but more focused feedback. At the same time, you can quietly extend tasks for confident movers by adding an extra step, a change of direction, or a simple rule to remember. The activity looks shared, but the demands are not identical.

Staff also need permission to slow down for certain children. If the timetable is packed so tightly that nobody can take an extra thirty seconds to walk a route together or model “between the cones” one-to-one, the children who most need that support fall through the cracks. Sometimes the real differentiation is in the pace of the room, not in the resources.

Supporting spatial awareness at home

Parents see the same bumps and spills you do, but they rarely call it spatial awareness. They say things like “She’s always knocking things over” or “He can’t judge where his body is”. If you can help families notice those moments and use them gently, the child gets double practice without anyone feeling they’ve been handed homework.

Simple Family Spatial Awareness Activity Ideas

Family activities don’t need to be as formal as classroom activities. In a way, the more ordinary the activity, the better. For example, creating a “stepping stone” path with cushions in the living room, building a short tunnel with chairs and blankets, or playing a game of rolling a ball under the table and back again are all effective spatial awareness activities, but for the family, it’s simply playtime.

Everyday Language Techniques for Parents

Some families naturally use many spatial terms, while others use very few. When communicating with parents, you can make it easier for them: suggest they choose one or two words, such as “under” and “between,” and consciously use them for a week. Many parents prefer specific phrases rather than general advice like “use more spatial language.” This feels more like a small experiment they can try, rather than a judgment.

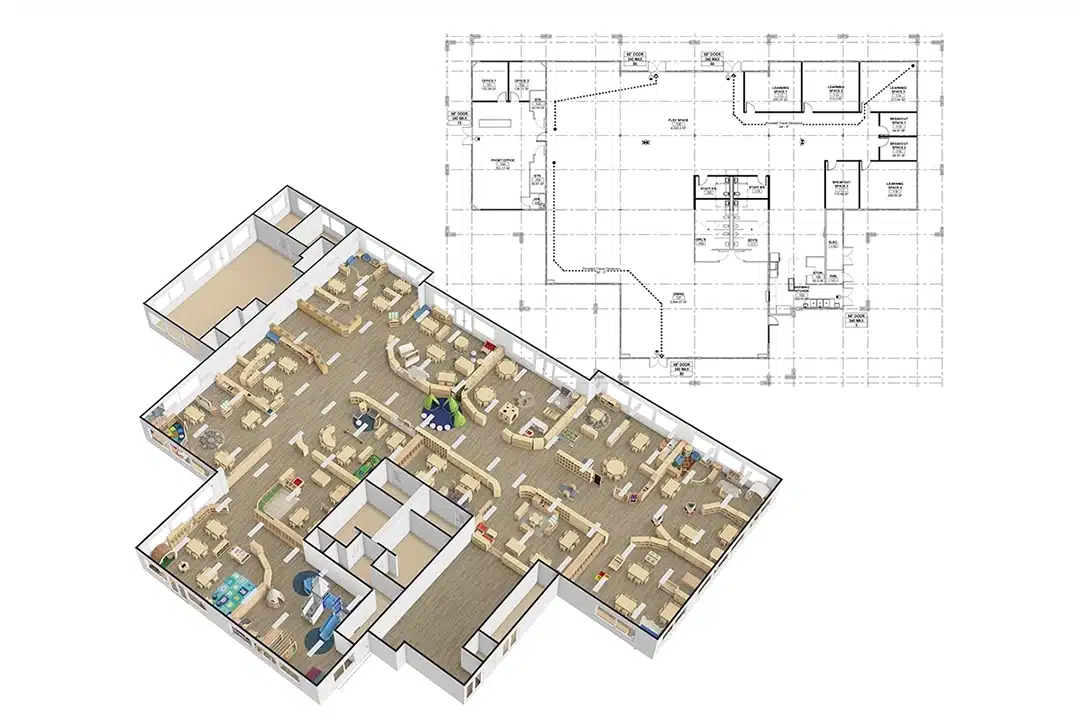

How preschool furniture design supports spatial awareness

When most people think about developing spatial awareness, they think of various activities and lessons. But in a preschool classroom, the furniture is key. Before children even hear any instructions, the bookshelves, tables, and rugs are already telling them what’s possible, where they can go, and how their bodies need to adjust. Good preschool furniture design is more than just “looking pretty”; it subtly shapes children’s activity patterns throughout the day.

If you observe your classroom with this in mind, you’ll notice some different things: narrow areas where children constantly bump into things, neglected corners, and shelves that make the space feel cramped or spacious. The same furniture, with just a few adjustments, can transform chaos into fluidity, giving children hundreds of extra opportunities to practice moving in space without adding any spatial awareness activities to the lesson plan.

You can think about furniture in four simple lenses:

- Clear learning zones

Use low shelves, tables and area rugs to create clear zones and natural pathways so children learn where activities start, end and how to move between them without constant reminders. - Right-size tables and chairs

Chairs, tables and open shelving at true child height let children sit, stand, push in, reach and put away on their own, turning everyday movements into small, self-directed spatial practice. - Moveable modular units

Lightweight, modular units on safe castors make it easy for staff to open a large space for a Spatial Awareness Activity one moment and re-form smaller zones for group work the next. - Safe, stable pieces

Stable, tip-resistant pieces at sensible heights keep children safe, maintain clear visibility across the room, and give a reliable “frame” for children to lean on, climb around and judge distance against.

Selecting Equipment and Resources for Spatial Awareness Activities

Once the furniture is properly arranged, equipment becomes the next crucial factor. This is often where administrators feel overwhelmed, faced with a bewildering array of plastic toy catalogs, limited budgets, and the pressure to have everything. For spatial awareness activity equipment in kindergartens, you can start with a few simple categories: core equipment for daily use, outdoor auxiliary equipment, low-cost supplementary equipment, and quality standards that help control cleaning and replacement costs.

The good news is that many of the best tools for spatial awareness activities are not complicated. Building blocks, cones, mats, tunnels, hula hoops, and various balls are sufficient for most indoor and outdoor play needs. The key question isn’t “What else can we buy?”, but rather “Do we have the right quantity and quality of essentials, and are they easily accessible to staff?”

A simple way to think about it:

- Core indoor kit

Blocks, cones, mats, and short tunnels that you can pull out quickly for building, path marking and small indoor movement games. - Outdoor movement kit

Hoops, larger cones, balance beams, and stepping stones that let children run, weave, jump, and balance safely in bigger spaces. - DIY and low-cost materials

Floor tape, cardboard boxes, fabric strips, and plastic bottles that can become lines, tunnels, islands, and targets for home-made spatial awareness activity setups. - Easy-access storage

Open tubs and low shelves so children and staff can reach, carry and put equipment away without squeezing through tight gaps. - Durable, easy-clean pieces

Wipeable, sturdy items that survive heavy daily use and quick cleaning, so they stay in rotation instead of living “out of action” in a corner.

conclusion

If we review everything we’ve discussed so far, a simple truth emerges: children don’t develop spatial awareness through one-off, special activities. They build it gradually through dozens of small, repeatable opportunities every day, using their own bodies to judge distance, position, and direction. Good spatial awareness activities don’t need to be fancy. They should be simple, easy to repeat, and easily integrated into the daily routines of the classroom.

If you’re looking for the next step and don’t want to overwhelm anyone, start by choosing one daily activity and one specific exercise. For example, you could focus more on language guidance while tidying up toys, or schedule two simple obstacle course exercises each week. Let the children get used to these activities before adding more. When the environment, the adults, and the daily rhythm all convey the same message—that your body’s position in this space is important, and you have time to explore and understand it—spatial skills will develop slowly and steadily.

FAQ: Quick Answers for Busy Managers

Common questions about implementing spatial awareness in early years settings.

How often should we run a spatial awareness activity?

Little and often beats a big “special” session once a month. Aim for one focused activity most days (5–10 minutes) and layer spatial language into normal routines like lining up or snack time. Consistency matters more than length.

What if our room is small and crowded?

Yes, you can still work on it. Tight spaces make clear zoning even more important. Use tape or rugs to mark paths and lean on activities that don’t need much floor space—puzzles, block challenges, or “Simon Says” with positional words.

How do I know if an activity is actually helping?

Look at the task: If children are judging relationships (over, under, between, next to), it’s working. If they could do it with their eyes closed or without referencing space, it’s likely just about stamina or rules.

What does “poor spatial awareness” actually look like?

It means a child regularly misjudges boundaries. You’ll see more bumping into furniture, knocking things over, confusion with positional words, and extra effort with puzzles compared to peers. It’s a brain-processing factor, not laziness.

What are some everyday examples?

Stepping over a block instead of kicking it; pushing a chair back just far enough to stand; placing a puzzle piece in the correct gap; or parking a toy car between two others without touching them.

Is spatial awareness a symptom of ADHD?

Difficulties can appear alongside ADHD, but they are not a standalone diagnostic symptom. If attention and spatial skills are both concerns, suggest parents consult a professional rather than trying to label it in the nursery.

What are broad examples of spatial skills?

Skills include judging reach, rotating shapes mentally, following complex directional instructions, copying block models, reading simple maps, and navigating crowds without bumping into others.