Part 1: Why Larger Classroom Communities Work in Montessori

Large classrooms with strong teachers lead to great outcomes for Montessori children

*Quick!* Would you choose a small classroom of 20 students or a larger one of 30 students for your child?

If you are like most parents, the answer seems obvious: smaller class sizes are always better, right? At least that’s the common wisdom: we’ve all read about teachers’ unions and parents protesting increasing class sizes during state budget cuts, and deploring the decline in learning that happens when one teacher has to manage 35 or more students in one public school class. One of the key appeals of private elementary schools, and one selling point of high-quality preschool programs, are smaller class sizes.

Class size and traditional education: smaller is likely (somewhat) better

For traditional programs, the research seems to suggest that smaller class sizes are positively correlated with better learning outcomes (see a good, balanced summary of the relevant research).

When you consider how a traditional school program works, this makes intuitive sense. In a traditional classroom, a teacher directs the learning of all students in a single-age environment. Much of the time, the entire class is working on similar learning goals: they all work on addition in math, or study how to write a paragraph in language arts. The adult’s role is to to transmit knowledge: she’s a teacher in the traditional sense of the term. She’s also in charge of checking and correcting student’s work, and spends a significant amount of time on managing her classroom, providing motivation and validation to students, calling students to attention, mediating conflicts, and so on.

With one teacher transmitting uniform knowledge to a large class, all at the same time, fewer children mean the teacher has more time to spend one on one with each child. It also means that in the group of students, individual students will be less likely to be “left behind”. Also, with fewer children, there’s a lower likelihood of too many challenging children distracting the teacher away from teaching as she needs to manage more difficult children while teaching the entire class. This is what the research seems to indicate: a significant reduction in class size (say, from 40 to 27 or from 22 to 17 in some of the studies) does improve achievement (in the range of three months of learning progress over a four-year period)—assuming the quality of the teachers stays the same.

Class size in Montessori: bigger (within reason) is better

Montessori functions very differently from traditional education—with the initially surprising result that larger classroom communities at the primary (ages 3-6) and elementary/middle school level are generally recognized by Montessorians to function better than smaller class sizes. (Note that the same does not apply for infant and toddler classrooms, where we keep student-teacher ratios purposefully in the 1:3 and 1:6 range respectively.)

Here’s what Dr. Maria Montessori said about class size:

“We consider that in its best condition, the class should have between 28-35 children, but there may be even more in number.”

What about a Montessori setting can make bigger classes work better than smaller classes? Here are a few points to consider:

The role of materials and the Montessori adult as guide, not a traditional teacher. In traditional education, the teacher teaches. In Montessori, the teacher introduces the child to a material through a presentation (e.g., a three-period lesson with the Sandpaper Letters in Primary), or offers thought provoking information(e.g., the Great Lessons in Elementary). This lesson is just the beginning! Once a child has received a lesson, she learns the skill or content through independent work with the materials. For example, a primary child may trace the Sandpaper Letters, over and over again, as she repeats their sound. Two elementary students may study the Fundamental Needs of Man materials, and do research on how people obtained shelter, food, clothing and transportation with books in the classroom library (or books gathered at an excursion to a local public library). The materials usually have a built-in control of error: a cylinder won’t fit into the Cylinder Blocks when it’s not the right size, the Bells won’t match if one pair is off and the child will run out of counters if their count is off on Cards and Counters. This control of error enables the child to correct his own mistakes and move on, without needing the help of a teacher to check his work and tell him how to fix it. Thus, in Montessori, the adult acts a guide who establishes the contact between the child and a material/topic that will offer the child an experience through which they will learn.

The role of peers in the mixed-age Montessori community. In traditional education, where children are in classes with same-age peers the opportunity for peer-to-peer learning and mentorship is limited. When all the children in a class are the same age, the traditional system requires teachers to “teach down” as abilities naturally vary between children. This pushes children too fast in some areas while leaving them bored in others.

In Montessori, we purposefully create mixed-age classroom communities: for Primary, children ages 3-6 are in one class; during Elementary, 6-9 year olds are joined in Lower Elementary and 9-12 year olds in Upper Elementary. This allows children to learn from each other, which benefits both the younger and the older children.

- Younger children can get help or even receive lessons from older peers. This helps with motivation, as the 4-year-old intuitively understands that he can and will soon read as well as his 5-year-old peer. It can also improve teaching: an 8-year-old who recently learned to master abstract addition into the thousands is often surprisingly capable at untangling problems in a 7-year-old’s thinking about math: she just overcame the same challenges a few months ago herself!

- Older children who give lessons or edit the work of younger children experience the benefit of built-in reviews of what they have already learned. For instance, whereas in traditional schooling children will most likely only cover adding fractions with different denominators once at age nine, in Montessori they’re likely to be called upon at age 10 or 11 to help a younger peer to master this concept. By explaining what they know to their younger peers, older students are actively reviewing their knowledge. They discover any gaps in their own understanding (in a non-threatening, non-pressure charge way—much better than failing a retest!), and then can get the help they need from their teacher. Teaching their younger peers also improves the older children’s confidence: they experience just how capable and knowledgeable they have become with all the hard work they put in during the preceding years.

In the Montessori elementary class, children learn that when they need help, they should ask themselves first, then a peer, then an older or more skilled mentor. Only when all that fails does the teacher get called upon. This reliance on oneself and one’s own initiative to ask a peer produces great learning outcomes—and, as a side benefit, it also strengthens children’s leadership skills!

The presence of concentration and child-initiated, intrinsically motivated work in Montessori. In a traditional school setting, motivation often happens through extrinsic rewards and punishments—everything from gold star charts and classroom pizza parties, to bad grades and trips to the principal’s office. One of the teacher’s roles is to dole out the rewards and punishments, to impose extrinsic discipline (e.g., getting children to not talk to peers and instead sit still and pay attention)—in a word, to get children to obey.

In Montessori, our goal is to connect each child with work that challenges him or her at just the right level—work that the child eagerly and with internal commitment completes, without outside incentives or direct supervision provided by the adults in the room. When you observe in a well-established Montessori classroom, you’ll see children deeply focused on chosen activities. You’ll also see them move about the room purposefully, working together in small groups, discussing their work in low voices. They’ll sit at little tables, or curl up with a book on a beanbag, or sit at a rug on the floor with some big work. Because the work is meaningful, because the children gain joy from doing it, because their natural needs are met (they can talk, they can move!), the teacher supports the development of internal discipline —and has more time to present lessons. In addition, while she teaches one group of children, the others don’t just sit by idly, daydreaming or doing “activity centers” or other busy-work jobs. Instead,they continue to learn and progress independently!

(This state of what Dr. Montessori called “normalization” doesn’t happen instantaneously in new classrooms. Initially, the teacher has to play a much more active role—which is, in part, why we typically start new rooms with fewer children. More on that in Part 2 of this post.)

It may sound counter-intuitive but to reap the full benefits of peer learning and independent exploration, it is often advantageous to have bigger class sizes. Too many adults in the room leads children to look to their teachers too much for guidance—when they could help themselves or learn from their peers. Also, teachers with too small a group of children may be tempted to teach too much—and become more like a traditional teacher, rather than the Montessori guide we want them to be.

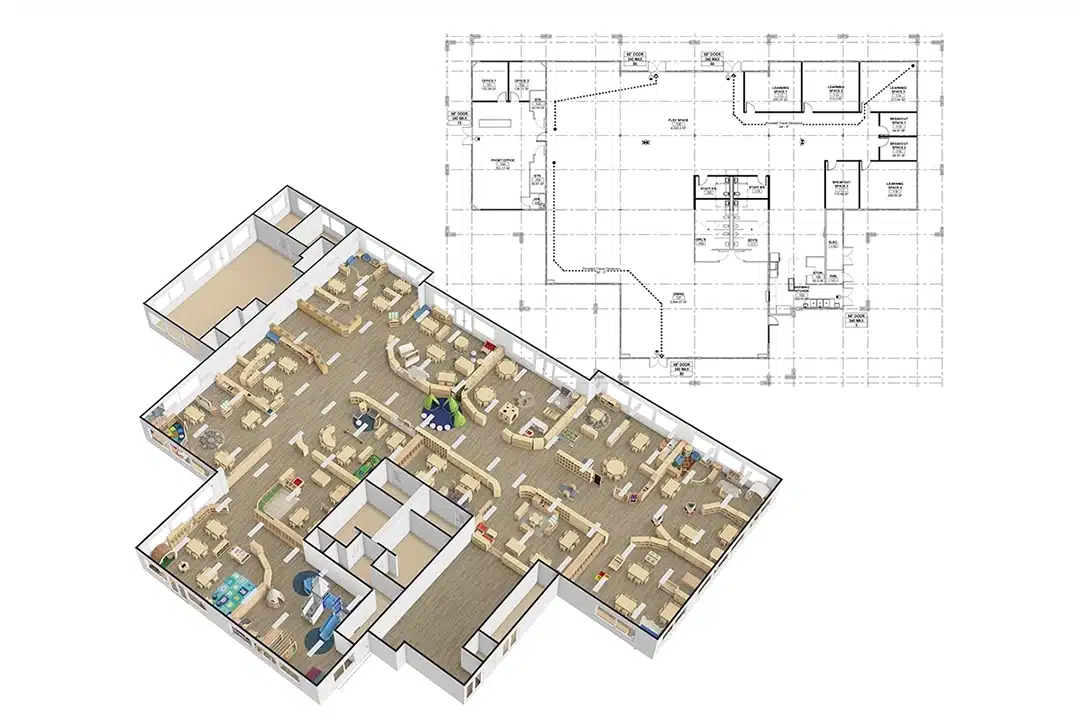

The importance of space for materials. A Montessori classroom needs a certain footprint to accommodate all the materials that must be in a quality Montessori environment—and all those materials take up space. In part why we generally don’t offer classrooms of fewer than 20 students, and aim for rooms sized for 24 or more children.: Rooms sized right to make a class of 20 economically viable feel cramped and can stifle children’s free movement. It is also why the large 30+ student rooms often have a more open, airy, inviting feel. There is still only one set of material of each type (with the exception of a few often-used materials, such as the math Stamp Game and the Small Bead Frame). With a larger room footprint the rooms feel more spacious, even if the space per child remains the same. Larger rooms may also have space for extra items, like a sofa for lounging, a music corner, or a free-standing kitchen work table that just might not fit into a 20 student room.